There is an unfortunate constant feature surrounding the figure of Julio Sosa: a certain incongruity. The legend that casts light on Sosa regularly shows these time imbalances, forced to tell us about the success of a man that would keep putting back the clock and yet died a death that was ahead of his time. A life that cherished by then obsolete social values, and a “rock-star” death, when no rocker had yet passed away. A reactionary, yet an avant-gardist. Where do all discrepancies converge to make him one of the greatest figures of all times? A deep study into the contradictions of Buenos Aires is called for, as well as into those reflexes that, now and then, twist the logic of cultural trends

There is an unfortunate constant feature surrounding the figure of Julio Sosa: a certain incongruity. The legend that casts light on Sosa regularly shows these time imbalances, forced to tell us about the success of a man that would keep putting back the clock and yet died a death that was ahead of his time. A life that cherished by then obsolete social values, and a “rock-star” death, when no rocker had yet passed away. A reactionary, yet an avant-gardist. Where do all discrepancies converge to make him one of the greatest figures of all times? A deep study into the contradictions of Buenos Aires is called for, as well as into those reflexes that, now and then, twist the logic of cultural trends

We will need to yield to his overbearing charisma, to the devastating energy of that tango bravado that managed to struggle against an inexorable future.

A timeless idol

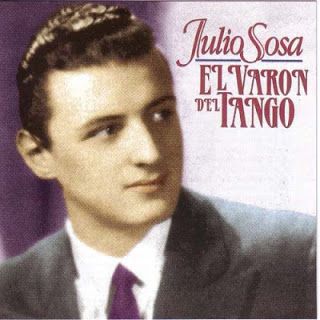

The passing of time blends hues in and bridges generational gaps. Beyond preferences, today we listen to Julio Sosa’s music in the same way as we listen to Goyeneche, Edmundo Rivero and Gardel, since all in all, they are all part of our history, which leaks into the present in minute doses of “porteñidad”. But unlike the rest of the performers (including the Polaco, whose memory has recently discovered an affective bond with the young), the “Varón del Tango” had his popular peak as he placed himself outside the mainstream, refusing to reconcile his career with the incumbent trends.

He went for the Buenos Aires mythical past (he adopted this city as his own, in spite of his Uruguayan nationality) from which he would approach a sort of cultural revisionism. During the “Club del Clan” heyday, against the incipient feminist movements and the industry “young” boom, Sosa clung to “the old” and prevailed. The city preferences and influences were being “internationalized”, yet he attracted crowds with his romantic macho hallmark. A model that, despite that virile, conservative image, was socially vanishing, giving way to new sexual revolutions.

Sosa would convey – to quote the rock band Bersuit Vergarabat- a “porteñidad al palo” [hot porteñidad in English], a Buenos Aires self-assertion argument that promoted the comeback of earlier values, in front of the “queer new wave” [as he roughly put it in an interview]. Millions of Argentinians followed him in that fleeting crusade. His first appearances with the Francini-Pontier orchestra welcomed a slightly humor-filled tone, and his baritone voice was perfectly compatible with that lost “arrabal” spirit. Later, against all expectations given his blooming career, he adopted a new identity: that of the man suffering over unrequited love, the honest nostalgic man that expressed his failure firmly and dramatically; and he prevailed here too, leaving his stamp in tangos like “Madame Ivonne”, “Qué falta que me hacés”, “La casita de mis viejos” and “El último café”, to name only a few. He was not supported by a new repertoire. It was the moral reserve of a way of life that began to extinguish his most archetypal vital signs.

Sosa would convey – to quote the rock band Bersuit Vergarabat- a “porteñidad al palo” [hot porteñidad in English], a Buenos Aires self-assertion argument that promoted the comeback of earlier values, in front of the “queer new wave” [as he roughly put it in an interview]. Millions of Argentinians followed him in that fleeting crusade. His first appearances with the Francini-Pontier orchestra welcomed a slightly humor-filled tone, and his baritone voice was perfectly compatible with that lost “arrabal” spirit. Later, against all expectations given his blooming career, he adopted a new identity: that of the man suffering over unrequited love, the honest nostalgic man that expressed his failure firmly and dramatically; and he prevailed here too, leaving his stamp in tangos like “Madame Ivonne”, “Qué falta que me hacés”, “La casita de mis viejos” and “El último café”, to name only a few. He was not supported by a new repertoire. It was the moral reserve of a way of life that began to extinguish his most archetypal vital signs.

Other aspects have helped build the myth: the man with humble roots (with an illiterate father and a maid for a mother; a man who had worked as a shoeshine boy in Montevideo) who took by storm Buenos Aires’ glamour scene surrounding the tango lifestyle; the night owl; the lover that was always ready for a fight. He lived, unintentionally, the creed that would be taught by punks many years later: to live a speedy life, to die young. He died at dawn, high speed driving, after a night among women, friends, and alcohol.

In view of such a life, musical debates (Was he better than Gardel? Was his voice limited to few tones? Did he sing out of tune?) have lost ground. Today the big picture is distorted. His physical farewell gathered 200,000 people along Corrientes Avenue. Forty years have gone by. Perhaps Pichuco was not mistaken in his statement: “You think that Sosa is the one who left? No, sir! It was a bit of all of us…”. Interestingly enough, the tango generation that worshiped him were young when the “right thing” was to be a Beatle fan or – in the worst cases- a Palito Ortega fan. For some reason, they stuck to that man who preferred to sing about old grudges. Today those people are from 60 to 70 years old. Rock has also ceased to be young.

In view of such a life, musical debates (Was he better than Gardel? Was his voice limited to few tones? Did he sing out of tune?) have lost ground. Today the big picture is distorted. His physical farewell gathered 200,000 people along Corrientes Avenue. Forty years have gone by. Perhaps Pichuco was not mistaken in his statement: “You think that Sosa is the one who left? No, sir! It was a bit of all of us…”. Interestingly enough, the tango generation that worshiped him were young when the “right thing” was to be a Beatle fan or – in the worst cases- a Palito Ortega fan. For some reason, they stuck to that man who preferred to sing about old grudges. Today those people are from 60 to 70 years old. Rock has also ceased to be young.